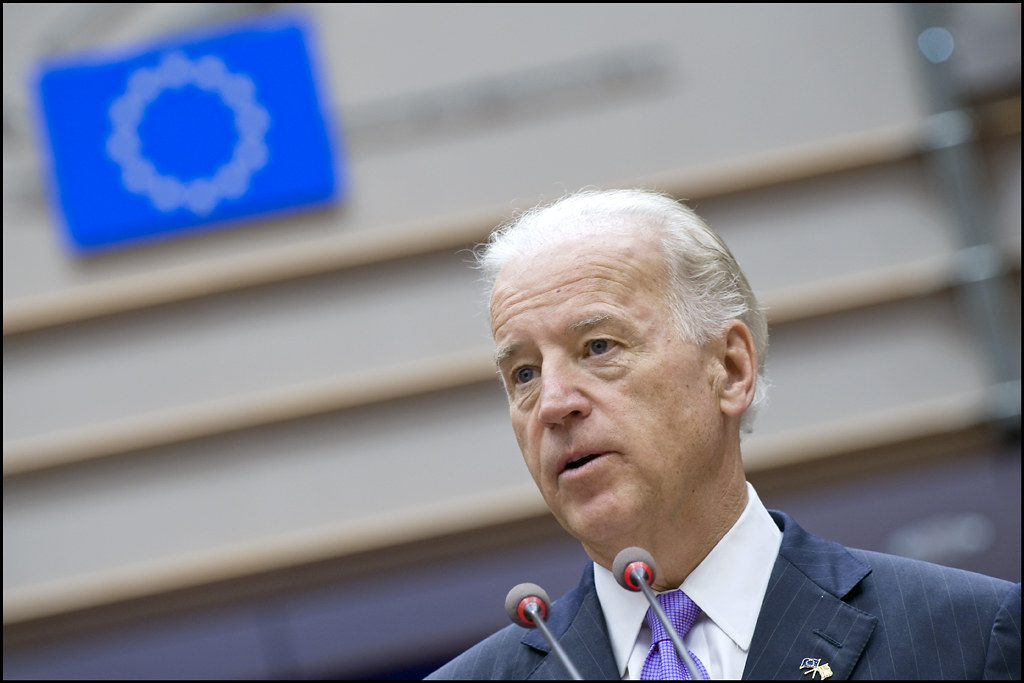

Cameron Munter on President Biden’s trip to Europe

Biden Comes to Europe. Author: Cameron Munter

There’s no doubt Joseph Biden is welcome in Europe. He’s a committed transatlanticist; his style is open and friendly; and most European leaders are comfortable with the broad contours of his liberal internationalist worldview. Most of all, he’s not Donald Trump, who baffled Europeans with his hostility and unilateralism.

But this visit – to Cornwall for the G-7, then to Brussels for the NATO summit, followed by a much-anticipated one-on-one with Vladimir Putin in Geneva – will not be sweetness and light. Or rather, look for two levels: on the surface, enormous relief that America and Europe can again talk to one another, and emphasize their common western history and approaches; but beneath the waves, there are currents that will make for some difficult navigation.

Twenty years ago, when I worked in the White House under Bill Clinton and then George Bush, developments signifying the unification of Europe (adoption of the Euro, accession of Central Europeans to the Union, the Lisbon Treaty) convinced us that we need no longer have a “Europe Policy” as such. Rather, Europe was becoming a partner in world affairs (and this was a benign globalizing world, as you will recall), working alongside America for free trade, free movement, free politics guided by wise diplomacy. Europe crafted politics to deal with its Eastern neighbors and planned its benevolent impact across the Mediterranean. The ever-closer Union would be an ever-expanding force for good.

Now two decades on the tide seem to have turned: with new leadership in China, free trade is under pressure; after Syria, free movement is the last thing most European leaders want; with the hardening of Russian intransigence, diplomacy in the region can be bitter and nasty. These are the currents that Biden will face during his visit.

I wish to point out three elements of the American approach which will have an impact on whether Americans and Europeans can, despite these challenges, work together more fruitfully.

First, China. My colleagues in Washington tell me that Europe is rarely the subject of the co-called “inter-agency” (the meetings, attended at various ranks, that are convened by the National Security Council staff and consist of representatives of federal agencies with international responsibility, including the departures of State, Treasury, Defense, Commerce and others, as well as the intelligence agencies and military). The Biden administration’s foreign policy experts are focused on China, first and foremost. There is no appetite to get back into the difficult problems of the Middle East, even if violence in Israel and Palestine demands attention and rejoining the JCPOA (that Iran Nuclear deal) is a stated goal; even if Biden has decided to meet with Putin, most experts consider Russia a problem to be managed than any sort of opportunity for (God forbid) a “re-set”. No: the defining topic of American foreign policy is China. And all other issues, including Europe, are seen through the Chinese lens. In fact, the question for the Americans is just how relevant Europe is in the looming struggle with China. As the American security expert Jeremy Shapiro wrote in Politico, “Europe is not the solution to America’s all-consuming China policy obsessions, but it’s not the problem either.”

Second, multilateralism. Donald Trump was so extreme in his rejection of working with others that traditional friends of the United States were enormously relieved to see him go, so that the “liberal international world order” in all its multilateral splendor could be restored, or at least, stop being dismantled. But this too is not simply a return to an imagined post-war harmony. There are a number of reasons for this. The Europeans allies, once burned by the rise of Trump, are not sure that he might not return, so commitments to multilateral leadership under Biden might simply be washed away in a few years. In addition, there are real differences in the way Americans and Europeans see multilateralism. To listen to Secretary of State Tony Blinken, you might believe that American multilateral efforts are actually a gathering of opponents of Chinese bad behavior, from the Quad (the newly empowered semi-military grouping of the U.S., Japan, Australia, and India) to NATO (assessing the new military challenges of great power competition, from hypersonic weapons to cyberattacks). That’s not necessarily the way that many European leaders see multilateralism; they would rather emphasize rules that protect the weak against the use of arbitrary power by the strong, and address transnational issues from climate to health to digital governance. Yes, the Americans aren’t uninterested for these transnational issues as well; after all, why meet with Putin at all if you don’t want to find some sort of common ground, whether it be preservation of peace in the Arctic or climate and energy challenges? Still, this is where I suspect we’ll see that differentiation of surface comity from deeper substance: Biden will likely depart Europe after mutual declarations of agreement on the great issues of our day, but I fear that we may see a lot of declarations, study groups, and long-term commitments rather than a real meeting of the minds on what multilateralism is for and how it should be used.

Third, history has not ended in Europe. It may have been a clever stratagem to signal to the Germans that they would not pay a significant price if they complete Nordstream 2; clearly, the tradeoff will be increased American pressure to play tough against China. But it’s hard to imagine that the security of Ukraine and NATO’s eastern members will be improved by this kind of deal. One can talk about Europe as a unit, but Nordstream is just one example of how divisions in the continent are becoming manifest. Germany exports a great deal to China. Countries like Austria, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia depend on supplying German exports for their own prosperity. Britain’s future and status are uncertain. France and Italy have plenty of issues to resolve, and let’s not even begin to discuss the curious cases of Hungary and, in different ways, Poland. It may be convenient to think of Europe as Brussels, with the occasional nod to Berlin or Paris; but if, for example, the Americans are serious about lining up support for Taiwan, they’ll hear different answers from Czechs than from Spaniards. Add to that other unfinished business: the Balkans have made little if any progress in the last decade toward EU membership or solving intractable problems. It may seem to American and European leaders alike that there’s not cost in ignoring the fact that stasis in Bosnia does not equal stability. Must we see violence before we focus on the specific efforts that are needed there, and in all of Southeastern Europe?

Is it all gloom and doom for this first visit of the new American president? No, because goodwill matters, the economies of the transatlantic world are likely to boom in coming months, and pandemic seems to be fading (at least in our privileged part of the world) and fighting in Luhansk or Nagorno-Karabakh or Gaza seems not to be totally out of control, at least not yet. The question is whether the visit of Joseph Biden to Europe this week can set a course in which fundamental challenges facing the Atlantic world can be addressed. Let us hope they can. But to do so, we need to look hard at how Americans and Europeans work together in the years to come.